6(C). Abuse by traditional healers

We are aware of traditional healers using sex as a form of treating women with mental health issues.

Photo: A woman with mental health issues, forced to live for many years in the Nsadzu settlement, Eastern Province, Zambia. 26 October 2012 © MDAC.

Photo: A woman with mental health issues, forced to live for many years in the Nsadzu settlement, Eastern Province, Zambia. 26 October 2012 © MDAC.

Several people told monitors that traditional healers had abused them. A community leader explained that, “a traditional healer will try to beat a patient, because always they associate any kind of ailment, like you know, [with] demon possession, and sometimes like a spirit has gotten into you, so you have to be beaten.” A representative of a disabled people’s organisation explained the types of cases which his organisation deals with:

We have received about four cases from different parts of the country where a person has been locked up for more than two weeks by a traditional healer, and of traditional healers chaining those mental health users to their own beds or to a tree. We are aware of traditional healers tattooing mental health users without their choice, throughout their body using a razor blade, and administering very itchy or painful medicine on those cuts. We are aware of traditional healers using sex as a form of treating women with mental problems. […] Some pour very hot water on them so that the ‘affliction’ comes out when they start going into fits.

It was not possible to verify whether the abuses alleged are currently happening, because the instance of people staying (sleeping overnight) in traditional healing centres seems to have reduced significantly over the last few years. Only two interviewees reported recent inpatient care at traditional healers; others reported short visits, or occasional over-nighters, or having the healer spend the night at the family home. Reduced levels of over-night stays decreases the risk of abuse within traditional healing settings, although it also increases the pressure on families, thereby elevating the risk of abuse at home.

Many people told monitors how unpleasant, and in many instances useless, the treatment given by traditional healers was, but did not report direct abuse. Three out of twenty people with mental health issues interviewed by monitors that they had been chained or beaten by traditional healers. Other informal interviews also revealed negative experiences. One interviewee told monitors that he was once chained for a week and was told that he would be unchained if he stopped being violent. He also reported that he was beaten. When asked whether he had the power to ask for the beating to stop, he responded:

Yes, I had the power to tell them that, stop beating me, but they were telling me that, we are beating you because you are violent, but you stop being violent, we are going to stop beating you. I said I will stop but you know, I was not. I was mentally disturbed, I was not controlling myself. Sometimes, it is just coming like that, then you will be violent, but later on the sense comes in and you stop.

Other people told monitors about their experiences:

When I was put in an enclosed space, they fed me in there, but they kept me there for some time, they bound my legs and my hands, they used inshishi [ropes, fibre from the tree]. I don’t know if it was two days or a day […]. The healing itself was traumatising, very traumatic.

28-year old woman with mental health issues

I slept, they wanted to chain me, the traditional healer. They wanted to chain me but I wasn’t violent, I was fidgeting because of the medicine I drank.

18-year old woman with mental health issues

I was given some liquids. One was mixed with chicken excreta. I never liked it. The one for drinking would make me vomit massively. I couldn’t refuse as I also needed to get better so I had no option even if it was uncomfortable. My sister made me go to get better. I can’t go back now, there was no help there, we were just giving money.

Young woman with mental health issues (exact age unknown)

Monitors visited four traditional healers and a spiritual healing centre. All the healers confirmed that they carry out forced treatment, and restrain “violent” people in distress, on the basis of ‘consent’ given by relatives who typically bring the person to the healer. All the healers confirmed that they would use chains if they had more space for inpatients. The expectation was that relatives would assist with chaining and tying. In the now-defunct Kitwe in-patient centre, monitors saw chains on a tree and pole, in October 2012.

Photo: A man holds up a chain, Kitwe traditional healing centre, October 2012. © MDAC.

Chaining

Prior to 2009 one traditional healer in Kitwe offered an in-patient service. A THPAZ representative commented: “There is one lady there who ties people with mental health problems, with chains […]; yes, that is our member unfortunately. Because of the unpredictable behaviour of some of the psychiatric cases, she chains them, but under human rights it’s illegal. You do not chain a patient against their will. […] Sometimes they run away and the healers lose a patient and the relative will question her, ‘Where has our patient gone to?’ So, she fears that they might run away, they might fight and beat the doctor. So she will chain them.”

One psychiatrist commented: “I went there some few years back, I found some patients tied, which is pathetic in our age […]. So we arranged that a clinical officer trained in mental illness goes there every week to unchain these people, give them medicine, but the traditional healing can continue, whether it is prayers or whatever medicines, but our clinical officer goes there once a week to give them psychotropic drugs and at least they are unchained. I think chaining at this stage is not good.”

There are no guidelines or other national policies regulating traditional healers. Restraints and seclusion are used arbitrarily, and provision of food and water is optional, as are toilets. The Constitution sets out that no person should be subjected to torture or inhuman or degrading treatment. The Persons with Disabilities Act mandates informed consent in the private sector as well as public services,90 and if it becomes law, the Mental Health Bill 2013 will regulate traditional healers.91

These current and potential laws may not be enough. The Zambian government is under a duty to immediately end all abuse and ill-treatment by traditional healers. As explained in section 4(C) above, international law binding on Zambia prohibits all forms of exploitation, violence and abuse including in the healthcare sector. Traditional healers are private individuals not carrying out their duties in the name of the State (unlike government-funded and run psychiatric facilities which are examined in section 7 of this report, below). The CRPD clarifies that the State is still responsible for eliminating discrimination against people with disabilities by any private entity, including traditional healers.92

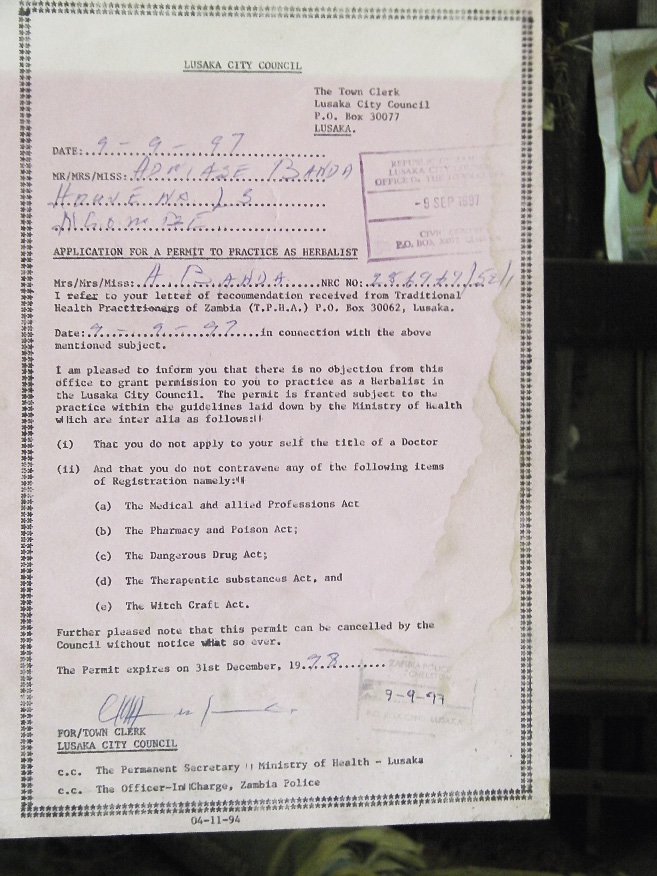

Photo: A traditional healer’s practice license,

Photo: A traditional healer’s practice license,

1 November 2012 © MDAC.

In Zambia, anyone can set themselves up as a traditional healer and charge for ‘treatments’. Some healers carry an annual trading license from the local government: accreditation that is not compulsory and amounts to nothing more than an administrative formality. Various professional associations including THPAZ are open to herbalists, diviners, spiritual healers, faith healers, traditional birth attendants and any other people who practise traditional medicine.93 The associations require various criteria to be met.94 The members are required to provide patients with information before treatment commences, to give patients the opportunity to accept or decline each treatment, to maintain confidentiality, and to refrain from advertising.95 A human rights officer from a disabled people’s organisation dismissed the current framework as ineffective, telling monitors there is a “serious need” for regulating traditional healers; a view shared by everyone who monitors spoke to in Zambia.

The president of THPAZ said even though his association has a self-regulatory scheme (consisting of a constitution and code of ethics), the government could establish conditions under which traditional healers should practice. He suggested collaboration with the local hospitals and psychiatric facilities, finding alternatives to chaining, and eliminating forced treatment. Additional emphasis could be put on obtaining informed consent for treatment from patients, including the right to refuse interventions, he said. This would preclude the reported practice of traditional healers covertly putting medicine into a patient’s food or drink, a practice condoned by the THPAZ code of ethics. He also spoke of the need to record treatments in writing, so that healers can later be held to account.

The WHO Regional Committee for Africa has recommended to African countries that they legislate to regulate traditional medicine within the framework of national health legislation and that they allocate funding to develop programmes.96 Zambia has no such legal framework, although its commitment to implement one was affirmed during a WHO regional meeting of ministers of health in 2013.97 Preparations are reportedly underway but as yet have not considered issues related to the treatment of people with mental health issues.98

Photo: Scarring. 2013. © MDAC.

Photo: Scarring. 2013. © MDAC.

The African Union Commission has also developed a framework for action and recommendations on combatting harmful traditional practices, which includes development of domestic laws and policies.99 The African Union has extended the decade of African Traditional Medicine (2001-2010) to 2011-2020.100 Various articles address the use of traditional healers for mental health issues in the region and the need for regulation.101

Internationally, there are few examples of codes of conduct for traditional healers in relation to mental health treatments.102 A code could establish basic minimum standards, and a governmental authority could provide a repository of promising practices where healers could provide examples of care which uphold human rights standards. A code could also lay out practice guidelines on how to manage emergency situations where someone’s life is at risk, particularly in the absence of any formal mental health services.

90 Section 27(d), Persons with Disabilities Act.

91 Clause 2(1), Mental Health Bill 2013.

92 Article 4(1)(e) of the CRPD.

93 Clause 3(1) and 5(1) of THPAZ Constitution, 2001.

94 Criteria include being an adult, law-abiding citizen, having at least primary education, and being a member of a recognised association of traditional health practitioners in the community of practice.

95 The restriction on advertising is intended to promote healers working on the basis of their reputation and to reduce opportunities for transient charlatans. Provisions are also made for the protection of children and patients of the opposite sex, with a relative being required to be present during treatment.

96 See WHO Regional Committee for Africa, Promoting the role of traditional medicine in health systems: A strategy for the African Region, 9 March 2000, AFR/RC50/R3. See also AFR/RC34/R8, September 1984, and the WHO Traditional Medicine Strategy 2014–2023.

97 MDAC/MHUNZA interview with a traditional medicine focal point person, WHO Zambia Country Office, Lusaka, Zambia: 4 February 2014.

98 Ibid.

99 Developed at a Pan-African conference on celebrating courage and overcoming harmful traditions, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 5–7 October 2011.

100 African Union, Draft Windhoek Declaration on the Impact of Climate Change on Health and Development in Africa CAMH/Min/Draft/Decl.(V), Fifth Ordinary Session of the Conference of Ministers of Health, Windhoek, Namibia, 17–21 April 2011.

101 Ae-Ngibiseet al., The MHAPP Research Programme Consortium, “’Whether you like it or not people with mental problems are going to go to them’: A qualitative exploration into the widespread use of traditional and faith healers in the provision of mental health care in Ghana”, 558–567. See also Sorketti, Zuraida and Habil, “The traditional belief system in relation to mental health and psychiatric services in Sudan”, supra note 71. A 2001 WHO review identified a variety of practices requiring regulation, licensing and registration, and the need for training in the field of traditional medicine: World Health Organisation, “Legal Status of Traditional Medicine and Complementary/Alternative Medicine: A worldwide review” (Geneva: WHO, 2001).

102 For example mental health/disability are not specifically referred to at all in the recent WHO Traditional Medicine Strategy 2014-2023.