7(E). Unlawful detention

If I annoy my brother he could go to the magistrates. Then I’m back in hospital.

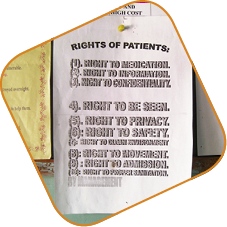

On closed wards most patients were detained without any legal authority, but expressed their desire to leave. They were therefore unlawfully detained as their liberty had been arbitrarily restricted.140 Patients were considered “voluntary” whether or not they wanted to be there, because their relatives had volunteered them to be detained for treatment.141 Hospital staff told monitors that patients sometimes did not know whether they are on a detention order or are entitled to walk out. Staff did not tell patients about their rights.

Photo: “Rights of patients” leaflet on a noticeboard on E Ward, Chainama Hospital, 30 October 2012. © MDAC.

Photo: “Rights of patients” leaflet on a noticeboard on E Ward, Chainama Hospital, 30 October 2012. © MDAC.

A staff member thought about educating patients of their human rights:

What you are proposing is a two way thing. You may come and educate them but that also has its own disadvantages, because once you open that Pandora’s box there will be a queue, even when it comes to eating beans. They will say we ‘were told that we are not to eat beans every day’. That will create a lot of problems because some of the patients are very intelligent, they are aware, not that everybody is not educated, just that the mental health problem has made them low. But when you open up their mind, you will see a lot of litigation.

Patients in closed wards were kept under lock and key.142 Monitors saw three closed wards in Zambia where 107 people were detained: the majority unlawfully deprived of their liberty. On open wards relatives had to ensure that patients did not leave the hospital: such situations also constitute detention. As far as MDAC/MHUNZA could establish, no cases have ever been taken to court about detention in psychiatric hospitals.

The Mental Health Disorders Act 1951 allows a magistrate to authorise detention in a psychiatric hospital for up to 14 days, “if satisfied upon information on oath that a person is apparently mentally disordered or defective and is (a) dangerous to himself or to others; or (b) wandering at large and unable to take care of himself”.143 No medical or other opinion is required. No opportunity is given in law for the person concerned to express their opinion, to say anything, let alone to have a qualified lawyer interrogate the evidence upon which the person’s liberty is removed and bodily integrity violated. There is no system of appeal to any judicial or semi-judicial body.

Photos: Ndola Male Ward (left) and Chainama B Ward entrance right). 24 and 30 October 2012 © MDAC.

Photos: Ndola Male Ward (left) and Chainama B Ward entrance right). 24 and 30 October 2012 © MDAC.

Monitors visited the magistrates’ court in Lusaka and found that obtaining a detention order takes a few hours after relatives of the patient-to-be complete a form and sign an affidavit. This affirms their name and address, their relation to the patient, the property owned by the patient, and that the relative believes the patient has a mental disorder.

An officer of the court is then supposed to conduct an interview with the relatives. The magistrate officer who receives applications and conducts such interviews informed monitors that typical symptoms of mental disorder reported by relatives include sleeplessness, moving up and down, extreme quietness and violence. She had five years experience of working in the sector, and said that she knew of only one application that had been rejected because the application was not from a relative.

Monitors concluded that judicial detention orders are exceedingly easy to obtain.

A detention order allows a person to be detained in a psychiatric unit for up to 14 days. During this time two medical practitioners are required to examine the patient and report back to the court on whether the patient is – using the statutory language - “mentally normal” or “a mentally disordered or defective person”.144 Monitors documented that this process was not followed. A magistrate officer told monitors that she had never seen any such assessment from doctors about persons subject to judicial detention orders. Staff at the hospitals confirmed this.

Instead of following the law, what happens at the expiry of the 14-day period is one of three things:

- the hospital discharges the patient; or

- relatives apply for another order from the magistrate; or

- the patient continues to be detained without any legal basis.

Staff told monitors that if they consider a patient to be well enough to be discharged before the expiry of the 14-day order they keep the patient detained until the 15th day. This makes no sense. If a clinical officer thinks the patient is not mentally well enough, the patient will remain detained until the clinical officer changes their mind. Outside Lusaka there are no psychiatrists, so decisions on detention are made by non-medically qualified personnel based on a rudimentary perception of symptoms, without any appeal or external review mechanism. A person who had experienced being a patient at a psychiatric hospital told monitors, “I live with this all the time. If I annoy my brother he could go to the magistrates. Then I’m back in hospital”.

In Livingstone, monitors saw an 18-year-old boy who was brought to the hospital by his father with a detention order. This was the boy’s second admission in two months. During his first admission he left the hospital and went home, so the father obtained a detention order to ensure the boy stayed in hospital. The father bought a padlock to lock the boy inside a room. Hospital staff told monitors that staff had asked the father to cancel the detention order but the father refused. The boy told monitors that everything was fine but that he was not allowed to move around.

140 Dr Simenda Francis estimated that one in ten in-patients had a detention order.

141 Relatives were required to sign “form 51”, which was used to consent or withdraw consent against medical advice. A psychiatric clinical officer said that if form 51 was not signed, patients could refuse medication. Another said that it was used as a ‘legal basis’ for forced treatment since relatives signed that the hospital could administer ‘life-saving’ interventions. However, they also reported that some patients do sign it.

142 Security guards were present at the gates to the wards of Chainama Hills Hospital’s acute wards and Ndola wards. Some carried a baton and handcuffs. They said the baton was to deter patients from approaching the gates.

143 Mental Health Disorders Act 1951, sections 7, 8 and 9.

144 Ibid., section 10. See also the detention order form: the magistrate “may, in his discretion, himself interrogate the patient […] and shall, whether or not he makes such interrogation, direct any two medical practitioners to examine the patient.”