7(I). Outpatients: distance and cost

If I don’t have transport, I stop coming here. Then I relapse.

Previous sections of the report looked at issues within psychiatric hospitals. This examines challenges that people faced receiving mental health support and services in the community.

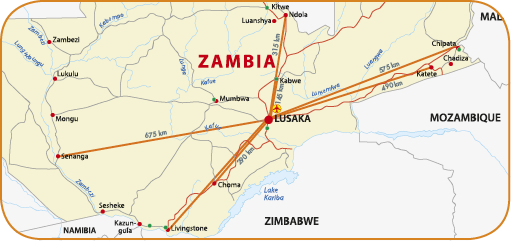

Picture: Approximately travel distances, by road, between Zambia’s provincial psychiatric units and Lusaka’s Chainama Hills Hospital. © MDAC.

Picture: Approximately travel distances, by road, between Zambia’s provincial psychiatric units and Lusaka’s Chainama Hills Hospital. © MDAC.

The CRPD requires governments to ensure that healthcare is provided as close as possible to a person’s home, including in rural areas. Similarly, the Persons with Disabilities Act requires the government to, “take appropriate measures to ensure access for persons with disabilities to health services that are gender sensitive and to health-related rehabilitation and shall, in particular, prescribe measures to […] provide health services as close as possible to people’s own communities, including rural areas”.151

Mental health provision at the primary healthcare level is practically non-existent. There is no system which tracks data, records services or provides information on community services.152 Access to mental health services is centralised in hospitals at eight sites across Zambia, a country with a landmass bigger than France.153 People and their families have to travel considerable distances to these hospitals. A patient from Petauke district will cover almost 200km to access services at Chipata Hills Hospital. Someone referred from Chipata to Chainama Hills Hospital would travel just under 600 kilometres.

In the absence of local services, patients and their relatives emphasised the time and money needed to travel to mental health appointments, in addition to the money required to cover the cost of appointments and prescriptions. People reported journey times to Chainama Hills Hospital of up to two hours each way at a cost of 50 Kwacha for return trip (approximately six EUR).

As a result some people simply did not attend mental health reviews. One patient explained, “If I don’t have transport, I stop coming here. Then I relapse.” Sometimes family members attend without the person affected. A staff member said that the absence of the patient, “puts us in a hard position – we don’t want to prescribe without seeing the patient, but we don’t want not to help”. During a mental health crisis, support is far away and inaccessible for most. The sister of a young man with mental health difficulties told monitors:

when he relapses, and when he’s violent, if our father is not at home, we run away. Hopefully he’s OK when we come back and we can try to bring him here, but it’s a long way and costs money, so that can be difficult.

Some hospitals have made limited attempts to bring mental health services closer to patients. For example, although medication is prescribed in hospitals, it may be administered at a local health clinic at bi-monthly reviews. At Lusaka’s Chainama Hills Hospital, staff told MDAC/MHUNZA that they carry out some community psychiatry every Friday in a few of the city’s 35 clinics. Similarly in Livingstone, mental health professionals coordinated with the St Francis Care Centre, an NGO, to join their mobile clinics once a week.

The Ministry of Community Development, Mother and Child Health recently appointed a mental health focal point to coordinate mental health services at district level. Plans were in place for all new district hospitals to have two or three mental health staff. Six such hospitals exist at the time of writing this report.154 The mental health focal point planned to conduct a situation analysis to understand what exists in terms of mental health services at the primary level. It seemed that funding to implement these plans was uncertain.

Any efforts to integrate mental health into primary health care should be encouraged. A shift from hospital to community-based care and training healthcare staff to offer quality mental health services can “contribute to the reduction of stigma and the promotion of human rights for people with mental health problems”, according to African experts.155

The Mental Health Bill 2013, if passed, requires each health facility to ensure availability of mental health services at all levels of care, improve financial and geographical accessibility and provide services that are acceptable and of adequate quality. It further requires mental health services to be provided on an equal basis with physical health care.156 The future National Mental Health Commission will have the task of facilitating the development of community-based mental health services, and the current institutional-based model of incarceration.157

151 Sections 20(2)(f). and 27(c) of the PWDA respectively. Picture: Approximately travel distances, by road, between Zambia’s provincial psychiatric units and Lusaka’s Chainama Hills Hospital. © MDAC. If I don’t have transport, I stop coming here. Then I relapse. Patient at Chainama Hills Hospital

152 Interviews with the Head of the Department of Mental Health at the Ministry of Health and the Mental Health Coordinator at the Ministry of Community Development, Mother and Child Health: 3 and 4 February 2014.

153 There were psychiatric wards at general hospitals in Mansa (Luapula Province), Kasama (Northern Province), Lewanika (Western Province), Livingstone (Southern Province), Ndola (Copperbelt Province), Kabwe (Central Province) and Chipata (Eastern Province). The North Western Province did not have any psychiatric facilities. In addition there were the dedicated Chainama Hills and University Teaching Hospitals in Lusaka.

154 Interview with the Mental Health Focal Point/Coordinator of the Ministry of Community Development, Mother and Child Health: 4 February 2014.

155 Lonia Mwapeet al., “Integrating mental health into primary health care in Zambia: a care provider’s perspective” (International Journal of Mental Health Systems 4 (2010): 21).

156 Clauses 16(1) and (2) of the Mental Health Bill 2013.

157 Ibid., clause 7(15).