This is No. 1 in a trio of OliverTalks posts about Butabika hospital, Uganda’s premier psychiatric facility, which I visited with colleagues last Thursday. It lays out how people are admitted and forcibly treated outside the ambit of a law, and how therefore people are unlawfully detained. The second part looks at discrimination against women patients. The third part looks at how medical treatment can constitute ill-treatment.

MDAC is currently carrying out three-week mission to Uganda, monitoring human rights of people in nine psychiatric hospitals across the country. I had the pleasure of flying into Kampala for four days last week to support our team: activists from the NGO Mental Health Uganda , Stephen Klein who is an experienced mental health inspector from the UK, and my colleague Eyong Mbuen who is coordinating our work in Africa.

We went to Butabika hospital, the national referral hospital for psychiatry (this causes much hilarity in staff meetings for my Hungarian colleagues: in Hungarian the name means “silly bull”). The hospital is located in the suburbs of the capital city Kampala and spread over several buildings set in a vast and green sanatorium-like campus. An oasis of calm as we walked in and sat in the comfy admin block talking to the director in an air-conditioned room.

Welcome! (c) MDAC

Welcome! (c) MDAC

Butabika has around 600 beds, but it contains around 700 patients – many share beds or sleep on the floor. Many newly-admitted patients are dropped off by families at the front gate, and many of these families are glad to see the back of their mentally ill relatives: stigma about madness is sky high in the villages. Many patients in Butabika have already seen traditional healers, consulted their local religious leaders, and searched in vain for non-existent community mental health services.

Luscious grounds, but on the wards it's a different story (c) MDAC

Luscious grounds, but on the wards it's a different story (c) MDAC

The average admission is six weeks. Some patients stay as little as two weeks. But some stay for much longer. One nurse told us she had been working there for 18 years. “There is a man with mental retardation who was here when I started working all those years ago, and he’s still here!” she said. I asked why. “He has no family,” she said. Despite the hospital having three social workers, the fact that this person’s family rejected him nearly two decades ago means that no attempt has ever been made to get him out of hospital and living somewhere in the community.

The right to freedom – like all other rights – should never be dependent on whether you have a loving family, yet that is how it works here.

The marketing indicates order (c) MDAC

The marketing indicates order (c) MDAC

Arbitrary and unlawful

The law currently in force is a 1938 Act which was fiddled around a bit by a civil servant in 1964: no substantive changes were deemed necessary in a generation, despite the ‘revolution’ of medication in the West. Obviously, a 1930s or 1960s statute contains little of relevance to contemporary psychiatry or human rights.

During our visit to the hospital we established quickly that the law is completely ignored. Some patients (no data was available but we estimated around one in five) were on “Urgency Orders” which means police brought the person in. The law allows “a police officer not below the rank of assistant inspector, any medical practitioner, or any chief” to forcibly take a “person alleged to be of unsound mind” to any facility if they are “satisfied that it is necessary for the public safety, or for the welfare” of that person. That’s it. Nothing else is required. The law says Urgency Orders last for ten days, but in practice nothing changes on the expiration of the order.

Given that patients are detained and forcibly treated without any legal basis whatsoever, or on the say of a police officer untrained in mental health, how is an admission decision made, we wondered? We asked this to the director. He told us that for staff to admit the person, the patient “has to be sick”. In addition the “mental symptoms should be severe enough for the patient to be admitted” and this is the decision of the doctor. That is it in terms of admission criteria.

When we visited the wards, we realised that it is actually nurses, not doctors, who make admission and treatment decisions. There are no written guidelines about admission procedure, or for that matter no written guidelines about anything related to patient care.

A patient is discharged, explained the director, “when the symptoms have gone down, the patient has developed insight and agrees to comply with their medication at home”. So in order to get out, the patient must admit they have a mental illness and agree to comply with medication. If these criteria are not met, it seems the patient will continue to be medicated to the point of submission. But we don’t know how long people stay in Butabikia. There is a register of all patients. The column on date of admission is filled in but the column showing date of discharge is often left blank. This is a seriously worrying omission of paperwork.

In international law, if a person’s liberty is deprived without a legal basis, then the deprivation of liberty is unlawful. No-one here gets a court review of detention. So we can confidently say that every patient in Butabika who wants to leave but is not allowed to, is unlawfully detained.

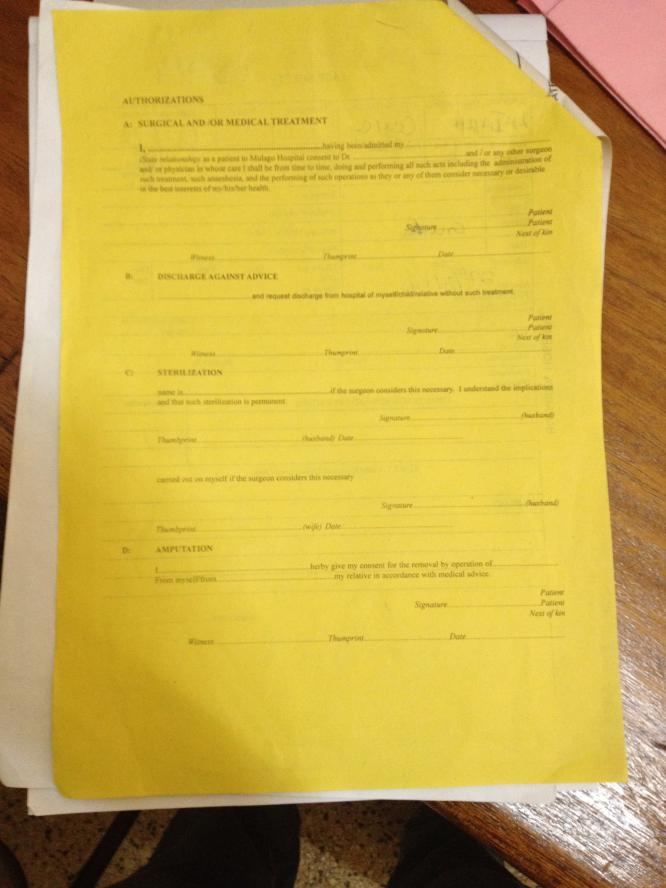

The paperwork bears little resemblance to the law (c) MDAC

The paperwork bears little resemblance to the law (c) MDAC

No inspections

The 1964 law says that the Minister of Health must appoint at least two people to visit psychiatric hospitals. This was, according to the Butabika director, done in the early 1970s, but has since fizzled out. None of Uganda’s psychiatric hospitals is visited by an independent body. Sometimes the Ugandan Human Rights Commission visits, but they told us that they need more training. They said they had visited Butabika recently and missed the main human rights abuses, focusing instead on why women bathed outside. Having seen the state of the inside bathrooms I can understand why people choose to bathe outside.

A new mental health act?

A Mental Health Bill was produced in 2009. A new draft was produced in 2011. Law-making is largely done by Uganda’s political elite without any public participation. There is a secret 2013 draft which the Butabika director promised to send us. The 2011 draft updates the concepts, but does not fundamentally change the way in which patients will continue to be detained and treated. There is no automatic court review of detention, for example.

Given that the current law is not in any way complied with, and that there is little understanding by service providers of human rights, is it going to be possible to enforce a new law? The bill could include a range of what I call compliance measures:

My worry is that a new mental health act is not going to change the patient’s experience because the current law is ignored, so why would it be any different with a new law? The question for MDAC is what we recommend to the Ugandan government and parliamentarians. One option is to make unlawful any detention and treatment – which as far as I know is not the position of any Ugandan NGOs. Another option is to recommend that the law somehow drastically reduces inpatient care and mandates regional authorities to shift their budgets from inpatient settings to community-based mental health care. There are likely other options. We haven’t yet decided, as we are still discussing with Ugandan colleagues. Your thoughts are welcome.

The government needs to map out where the needs are, instead of investing in outdated and abusive institutional confinement (c) MDAC

The government needs to map out where the needs are, instead of investing in outdated and abusive institutional confinement (c) MDAC