5(A). Key findings from 2003

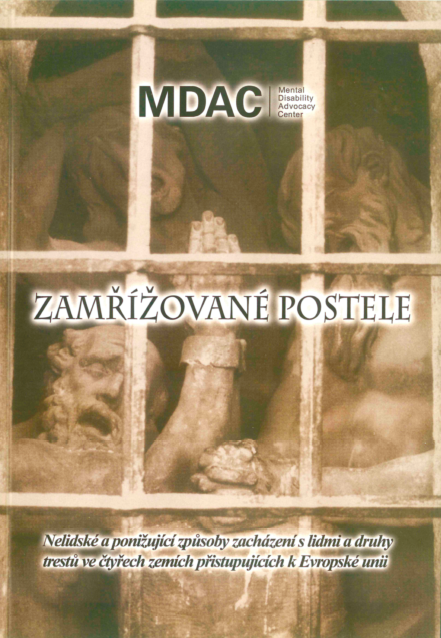

Photo: © MDAC

Photo: © MDAC

MDAC was refused access to visit Jihlava, Opava and Kosmonosy Psychiatric Hospitals, all of which had high levels of use of cage beds.

-

430 people had been placed in cage beds at Kosmonosy Psychiatric Hospital in the previous year, an institution with 500 beds.

-

10% of the 600 beds at Jihlava Psychiatric Hospital were cage beds.

-

At one children’s psychiatric hospital, two “small beds for very young children with nets” were in use, reportedly “to prevent these children from getting out”.

-

A seven-year-old boy was observed in a cage bed without any supervision.

-

Other physical restraints were in common use, including straps and straightjackets. People were restrained for extended periods of time, sometimes for days.

-

In 2002, a 14-year-old girl had died in a straightjacket locked in a cage bed when an iron bar from the frame of the bed fell on her. Rather than removing the cage beds, the psychiatric institution instead replaced them all.

-

The director of one social care institution had already banned cage beds eight years previously: “I simply threw them away,” he reported to MDAC. “Staff should know the client so well that they can predict a possible attack and prevent aggression.”

-

Independent inspections of psychiatric facilities in the country were not compulsory. Psychiatric institutions even refused access to the then Czech Commissioner for Human Rights, Jan Jařab.

In 2013, ten years after it reported on cage beds in Czech psychiatry, MDAC organised two follow-up monitoring missions to institutions in the country to find out whether there had been any progress. A decade on there remains a troubling picture. The overall numbers of cage beds in psychiatric institutions have been significantly reduced but many are still in use. Indeed, in one children’s psychiatric institution, they were reportedly only removed at the beginning of 2013. The reduced numbers of cage beds have not prompted any decrease in overall levels of coercion, which remains a hallmark of the overall psychiatric practice in the country. Other restrictive techniques including seclusion, physical and chemical restraints – all of which are abusive and amount to ill-treatment or torture – have become increasingly relied upon.

The intention of this report is call on the Czech Republic to take measurable steps to ensure that people in its mental health system are not subjected to abusive practices which are unlawful under international human rights law. To do this, the chapters are set out as follows. This chapter starts by providing the context of coercion within Czech psychiatry. It then presents the standpoints of experts in relation to torture prevention. Chapter 6 sets out the findings on the use of cage beds in eight psychiatric hospitals visited by MDAC monitoring teams. Chapter 7 goes on to present findings about the use of chemical restraints, straps, seclusion and other forms of coercion. It provides an overview of the perspective of staff working in Czech psychiatric institutions and their general disbelief that lower levels of coercion are either possible or desirable.

Leadership is required within governments and within the global psychiatric community to move beyond old models of managing people with mental health issues through coercive practices. To assist staff and policy-makers, Chapter 8 outlines several evidence-based approaches to reducing coercion, many of which can be achieved without much financial investment.

Photo: © MDAC

Photo: © MDAC

Photo: © MDAC

Photo: © MDAC