This blog post is the first in a three-part series based on a chapter I wrote in ‘Torture in Healthcare Settings: Reflections on the Special Rapporteur on Torture’s 2013 Thematic Report’. The book features contributions from over 30 international experts in response to Special Rapporteur Juan E Mendez’s 2013 Thematic Report on torture and other abusive practices in healthcare settings. You can read my chapter here, from page 247.

As I wrote in a previous blog post, I went to a conference a few months ago which sparked some thoughts about the relationship between world psychiatry and human rights. Professor Norman Sartorius gave a presentation (you can watch it here) in which he suggested that someone should develop a document setting out a hierarchy of rights for people with ‘mental disorders’. What would this hierarchy be, and would it be a good idea?

Professor Norman Sartorius

Professor Norman Sartorius

Sartorius asserted that rights cannot be implemented at the same time. He proposed the right to life as number one priority. If a person’s life is in danger, he said, the person should get the mental health treatment that will save his life, “not voting rights, which is something which comes later. There is a certain thing which you can do now and must do now.”

Interdependence of human rights

This statement is not only empirically untrue, but runs counter to established notions of interdependence of human rights provisions. It goes without saying that human right A can be implemented at the same time as human right B. The right to vote can and must be provided immediately. Equally, the right to be free from torture can and must be provided immediately. Coordination across government is necessary to ensure spread and avoid duplication (for human rights geeks, this is what Article 33(1) of the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities tries to achieve), but human rights is not a linear list.

Policy-makers are not supposed to check one human rights box before proceeding to implement the next one. Furthermore, the right to political participation for many people with psycho-social disabilities and people with intellectual disabilities, who have been denied that right, has an instrumental and expressive value. Not only is participation in a democracy one of the easiest rights to implement, it is one of the most fundamental in reversing the political invisibility of people historically invalidated by law and politics.

The WPA – time to engage with human rights

Norman Sartorius is not the only psychiatric leader calling for prioritisation. Writing in the Lancet in 2011, the immediate past president of the World Psychiatric Association (WPA), Italian professor of psychiatry Mario Maj also suggested a list.

Professor Mario Maj's hierarchy of rights for people with 'mental disorders'

Professor Mario Maj's hierarchy of rights for people with 'mental disorders'

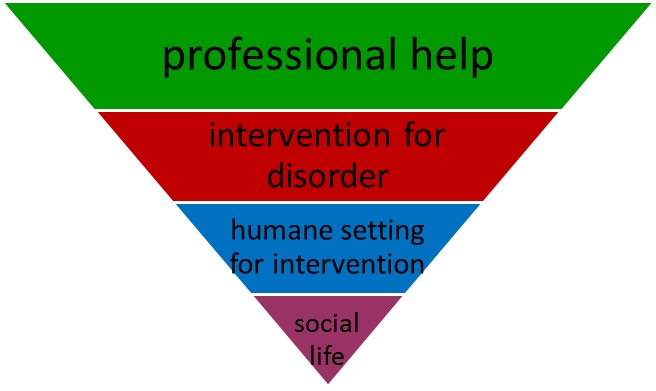

“The first indisputable right of a person with a mental disorder” according to Maj is quite a surprise. It is not the right to life. It is not the right to liberty and security, to food, water, shelter, or housing. It is not the right to be free from abuse and neglect. “The first indisputable right of a person with a mental disorder”, writes Maj, “is to find in the public health system a professional who is able to understand the nature of that disorder.”[1]

“A second unquestionable right of a person with a mental disorder is to receive an intervention for that disorder that accords with available research evidence, within the limitations of the local context.” It is also a right for the “disorder” to be “managed in a setting that is decent, humane, and non-abusive.” A fourth right is for the person with a “mental disorder” to have “a full affective and social life.”

The “most important right” for a group of people is an empirical claim that can be tested. One can ask the people concerned! Yet these statements cite no research evidence.

Dr Maj says that his view is “unquestionable.” He erects a Perspex screen between himself and other views. As president of the World Psychiatric Association he speaks a truth that cannot be questioned. His views also perpetuate an old-fashioned and debunked medical model of disability where the disordered mind (or brain?) is a machine that needs to be fixed.

Maj persists that mending the mind is not only a medical goal, but a pre-requisite to “a full affective and social life.” His worldview offends well-established notions of human rights, namely respect for diversity – including the right not to be ‘normal’, however defined – autonomy and the right to make one’s own decisions.

[1] Mario Maj, The Rights of People With Mental Disorders: WPA Perspective, 378 The Lancet 1534-1535 (2011).